Game Review: THE FINAL SPECIMEN Needs More Lab Work

A game got floated by our Scifi4me’s editor’s desk recently by an indie game company, going by the moniker of GigantoRaptor Games, asking us to give a review to their recently released title The Final Specimen in an exchange for a free copy of said title. On behalf of the video game division at SciFi4me, I would like to say, “Thank you.” I highly approve of, and recommend, companies — especially indie as well as full publication outfits — doing this sort of practice as a way to get websites, like our humble science fiction magazine here, to review games both new and up and coming, as well as established titles.

To be honest, this is the sort of the thing that happens in the film industry all the time, where a film company will give a free screening to a critic and allow them to have a review of the film ready before the film’s release, or at least very close to said release. So let me extend a hand from us here at Scifi4Me to the game developer community. We review all things entertainment, film, comics, books, television, and yes, even video games. I would like to once again thank GigantoRaptor Games for sending us their game to be reviewed.

Next I would like to establish some things about myself. We have a few people working in the video game division here in the underground cold war mad scientist SciFi4Me laboratory, and I would like to take this time to elaborate on why I felt that I had the appropriate background to review this particular game. My name is Casey Shreve, and I, like most gamers, have been playing games my whole life. I’ve been absolutely obsessed, not just with the games and how they play, but the deconstruction of games and their inner workings, finding out what makes up their composition and experiences. The intricacies of their stories married with the visuals and mechanics behind them. It is as fascinating of a field as it is an endless search of knowledge.

After obtaining a general Liberal Arts degree focusing on film, art, animation, and psychology, at the University of Kansas, I am now currently pursuing a degree in game design itself. I am one year away from graduating and have been studying heavily, pumping out prototypes, essays, mechanics tests, and all sorts of material, getting ready to build a team project that is dubbed “the capstone” in my major. Yes to graduate, you have to build a game by teaming up with 4 different departments at the school (animation, programming, art, and design).

Over this summer, the honors department at my college has just informed me that I have made the presidential honors list for my college, which is to say that I am now in the top 2% of students at of my school. I am expected to graduate with my degree in game design here this next spring. As Jim Sterling from the Jimquisition would say, and I’m paraphrasing here, “Hurrah for me.”

As per the major, I started off learning how to use GameMaker Studio to understand the basics of what games are and what is the mercurial substance that makes up a game. I then learned about code and java script (required in entry level classes, let alone my studies of C++ at the University of Kansas). Through my studies I’ve made pen and paper games, board games, and even card games on top of the digital video game medium. I then transitioned into using higher level programs such as my (current) go to software, Unity3D, and the much more unforgiving game engine, the Unreal Engine. I’ve studied many aspects of game design including things such as level design and mechanics as well as the never ending existential question of “what is fun”.

With this background and wealth of education into the field of game design, I felt that my qualifications matched well for giving critiques of the following nature.

Now that my background and information is out of the way, onto the review.

The Final Specimen

The Basics:

According to the studio’s website:

[su_quote cite=”Gigantoraptor Games” url=”http://thefinalspecimen.com/”]THE FINAL SPECIMEN is a 2D sci-fi/adventure game in the style of the classic platformers of the late 80’s/early 90’s. Packed with whimsical settings and eccentric characters, this energetic, challenging title brings a humorous and exciting take to old-school gaming. Its colorful, crazy world comes alive as you run, jump, and swing your way across a plethora of visually unique and thematically distinctive levels.

THE FINAL SPECIMEN is a game like no other. Each of its levels has a life of its own, each of its enemies a personality. The terrain ranges from the grassy to the mountainous to the aquatic to the mechanical. From rope swings to grappling hooks, there is no shortage of new tools you can discover to aid you in your progress. And if the ability to punch your enemies’ lights out isn’t enough, you can also collect ammunition – your own personal arsenal of pocket bombs.

The game begins when a young earthling is transported to a distant planet. After facing sudden assault from the world’s inhabitants, he soon finds out that his arrival is no coincidence. What he learns sets him off on a mission to prevent the annihilation of the planet – and the subsequent conquest of earth by a nefarious alien mastermind. You are the only human who has the power. You are the culmination of years of alien experimentation. You are THE FINAL SPECIMEN.[/su_quote]

Just from the website alone, you get the feel that there is a little bit of story going on, and even though the art isn’t well developed and far from polished, there is a mostly uniform aesthetic to the whole composition. I won’t spend much time on the art, which is amateurish, at best. My biggest critique is in the form of education. As you will find throughout this article, education is kind of the solution to many a problem in the massive field of game design. Education and practice.

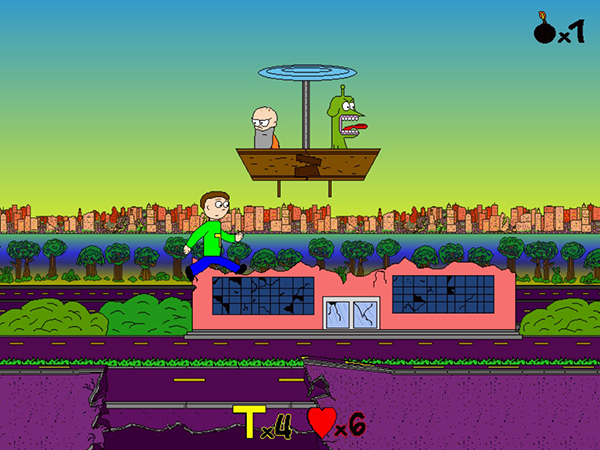

The characters in the game move unnaturally and the animation for each sprite is choppy and erratic. The hit boxes on the sprite are not very exact in many instances, causes a disconnect between what we see happening on the screen and what the system knows is happening. Visually, there is little distinction between characters in the game and the enemy encounters are very repetitive. There is also some camouflaging (in art, that means that the colors in a section of a piece of art are so similar between two adjacent objects that they blend in to each other, unable to tell them apart. The whole “polar bear in a snow storm” art gag when it’s just a blank white piece of paper.) That happens quite often in each scene as well, something that you need to think about when choosing colors and how those colors interact with the space that you put them in. For instance, a black bomb up against a black door or street texture.

Basic drawing classes that focus on still lifes (most classically known for being a bowl of fruit), and most importantly, life drawings (the study of the human figure in poses and motion) are paramount to any artist both professional and amateur. Decoding how the world puts shapes together to form organic matter that interacts with the inorganic takes a lot of time and it is scary how much harder it is than it sounds. I would highly suggest to the artist of the game to start taking life drawing classes at a local art supply store/community center/community museum/ or anywhere they are available.

Taking these classes will show the artist how the body moves, where the joints are located on the body, and how this interacts in space. It will also help with proportion and perspective when you create characters and put them in worlds. A solid foundation in art will help games develop a clean and clear visual spectacle for the player.

From the game’s website, one of the first things that I noticed right off the bat was the strange method of distribution. The company is selling the game for $10 per copy and are using Square to handle sales.

There’s kind of a good thing/bad thing happening with this idea to use a basic money processor to handle sales of your game instead of going out of a third party game distribution website like Steam, Kongregate, GoG, or Itch.io. One of the good things about it is that you can manage your own distribution fairly handily and cheaply. For a small studio with little to no recognition, where a producer and publisher (the people that fund game developers to develop games through loans and advances) will be impossible to find, finding your own funding is kind of paramount and a bit of a daunting task. Although sometimes, just like in the film industry, bypassing the need for producers or publishers can be a great way to unshackle a lot of game ruining micromanaging (or snubbing producers that think that there isn’t a market for X game, when there clearly is) as some larger video game designer names have done on crowd sourcing websites like Kickstarter.

The bad side of not using some sort of digital distribution is that your studio does not get access to long standing price data from games that are very close to yours. This information is invaluable to game developer companies. Staying competitive is a major key, and if you overcharge for your product, people simply won’t buy your content. Especially in a world where you have to launch a massive television advertisement campaign just to justify a $0.99 phone app. Even games that are free have a huge endless ocean of competition to just get played let alone marketed.

With that all said, for a company’s first ever video game, $10 is a pretty shameless price point. If you go on Steam and search for games that cost between $16-10, you’ll find remarkable games such as (if you haven’t played any of these, for the love of all that is holy, pick up these games!) Cave Story+, Shovel Knight, Rogue Legacy, Dust: An Elysian Tail (and another review Dust got from us back in 2012 can be found on this link), and a massive host of big name indie games, and a handful of AAA titles, that are tried and true both new and old staples of the video game industry. The games listed above are amazingly refined and polished video games. The premium price of $10 a copy is an insane price for a company’s first game, such as The Last Specimen.

To be frank and honest, I did not download the full game. I played the demo to see if it was something I should review or not, let alone install the full version on my machine. What I discovered in the demo was… well, to put it bluntly, a game that needs a massive amount of work before it’s ready to be sold anywhere. It felt more like one of the quick-fire three week prototypes that my peers would come up with in my rapid prototyping class. If anything, this game is a good proof of concept, but little, if anything, more than that.

Breaking it down:

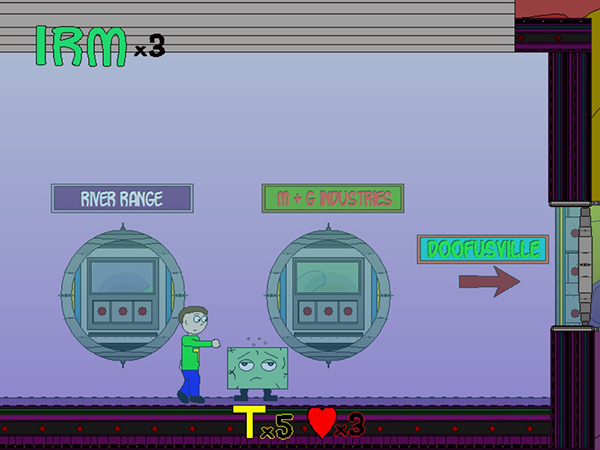

One of the major issues the game has, is conveyance. Conveyance, as it relates to game design, is the ability to express an idea to someone (other than yourself) in a coherent fashion. After playing the demo, I still have absolutely no idea what was happening moment to moment in the game. Controls were not intuitive nor explained and even though they are written down in the very brief manual, for the most part, the controls didn’t react very well when the buttons were pressed. They were sluggish at times with a slight delay between button press and character controller reaction, especially if there were a lot of things happening at once on the screen. Playing the game reminded me a great deal of a video that was made a long time ago from a famous animator who used to post glorious animations to a flash based website called Newgrounds, about the subject of conveyance and level design.

The video below has strong language, but I can not emphasize enough how important the topics are inside this video. The creator of the video is a well known animator that goes by Egoraptor, so yes, extremely explicit and strong language. But if you are learning how to develop games, this video should be a prerequisite before anyone even touches a computer keyboard. It is on point and nobody has ever really covered the subject so eloquently and completely as this video.

[su_youtube url=”https://youtu.be/8FpigqfcvlM” responsive=”no”][youtube = https://youtu.be/5svAoQ7D38k][/su_youtube]

One of the major challenges of making a game is teaching the player new things about your game. The Last Specimen puts you in their world, and then pretty much ignores the player entirely after that. In other words, it doesn’t teach the player anything about itself. You can take it or leave it. Even the manual is more of a sales pitch than an “about our game” explanation of mechanics. The other end of the spectrum, that many AAA studios have done to their games (as discussed in the video) is using tutorial levels and hand holding to tell people how to play their game, which is a major insult to a player’s intelligence. Doing too much to the point of annoying the player or not doing anything, both strategies are absolutely terrible design choices. Egoraptor gives probably the best argument about conveyance about eleven minuets into the discussion on game design where he talks about an old Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde game. You can see what I’m talking about in the video above or by clicking here to be taken to the exact point in time.

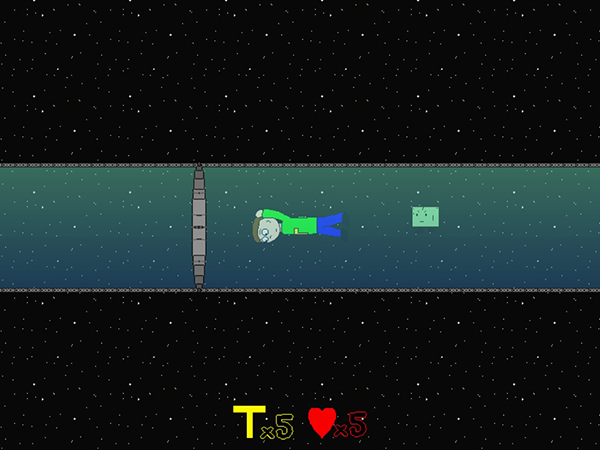

Moving on we get to the AI of the game. Enemies in the game had an wealth of problems. The first problem is that they didn’t have any weight or had any impact on the world itself, so the player can simply ignore nearly all encounters. Bosses didn’t really have any differentiation between themselves and the normal wash of enemy types, so the only way you could tell that there was a boss in front of you is that you couldn’t move the camera to the right any longer. Enemy programming was simply “notice the player > approach the player > attack the player” with only slight variations to that formula. Some enemies were simple hazard avoidance objects (don’t get hit by a car, for example) and those would move in an overly predictable linear direction towards the player without any deviation or surprise. These very basic AI systems, combined with extremely long levels create a rather bland gaming experience.

The camera itself had its own host of issues. Parts of the level were too tall for the camera to follow the player as the player went ever higher to progress forward. Enemies spawned in these locations went unseen and could damage you without anything displaying that you had been damaged or where that damage was coming from. As discussed above, there wasn’t any sort of scene transition when “bosses” were introduced, so it was incredibly hard to figure out the difference between a “boss” part of a level or any other area on the screen.

The UI (User Interface) was severely minimal. You have a bomb amount counter, a heart counter which displays how many hits you can take before you “die” (but so many things simply kill you in one hit that the hearts as a health mechanic are a little pointless), and some sort of “T” counter, whatever “T” is. I’m still not sure. It could be lives or maybe some sort of special attack… I have no idea. But as far as UI, that’s it. The images and count numbers are printed directly to the screen without any sort of well defined border, fan fare, or actual design mechanic other than the little symbol images and a number. Black text is used for the UI, as well is used for the bombs your character throws, which both blend into the levels and background, as dark colors are chosen for the levels with no separation between the game and the vague UI graphics.

Character controller is clunky at best. The code that defines movement is not very clean so activities such as jumping and fighting enemies becomes frustratingly difficult. There’s a lot of different “things” in the character controller that stand in conflict with each other. If you run up to an object that is classified as a ledge, you instantly stick to the ledge, even if you were just wanting to continue to travel forward, and the ledge is both not defined visually in any way on the screen nor is it placed in a height proportionate to the player’s height. “Animations” between player controller states (jump vs punch vs throw vs ledge cling vs walk) seem to constantly fight between each other and freeze constantly, often resulting in your character choosing the “stand still” animation quite often for nearly every task and activity.

Level design. Side scroller games, such as The Last Specimen, are entirely dependent on good level design. Level design will make or break your game, because in the end, that’s the only way for this type of genre to tell it’s story. Not to keep kicking the same example around, but the above video, with its in-depth look into the Mega Man franchise, takes a very detailed look into this exact style of scrolling video game story telling, both old and new (time relative to Mega Man games of that particular era).

The levels in The Last Specimen are not very well planned out. Levels themselves are impossibly long. There is no other paths for a player to take other than the golden path (the critically important and quickest path to get through and complete the level). The levels reminded me of an old cynical comedy game from Adult Swim that came out many a year ago called “Worst Game Ever“. They are long, bland, and highly repetitive with nothing really going on moment to moment. As I mentioned above, enemy encounters can mostly be ignored so the game quickly turns into “Press right arrow until you can’t go right any more, then push some other button”. With the character controller not having smooth controls, simple tasks such as jumping becomes a bit of a chore. Combined with the bad jump mechanics, the levels are designed with many instant kill pit-falls, so the game becomes frustrating to play very quickly.

Objectively, this game is far from a finished product, let alone something that should be up on the open market, asking for a price other than play time. As I said near the beginning, this is a proof of concept. A prototype of an idea, but the idea isn’t quite implemented just yet. The scope of the game is extremely large for the design of the product being sold, which results in the sort of discombobulated play experience we are given. A common phrase for that is “Running before you can walk.”

For the developers, and for all aspiring game designers, please remember that education is key. Learning how all of these different systems come together to make a play experience is essential to making these unique experiences that we call video games. I highly recommend anyone wanting to start designing video games to take some classes at a community college or find some other form of accredited course work. MIT has a free online audio lecture series (a microphone accidentally left on in one of their classes, no doubt). I do caution that there are scammers for game design education (including anything that has “Art International” at the end of the title or “Phoenix” somewhere in it… basically anything that’s the usual education scam of “online courses”).

Moving forward with The Last Specimen and games far after that, I have some suggestions that can better improve game design skills by leaps and bounds.

There are a great deal of textbooks you can buy to help you understand “what makes a good game”. One that I suggest is The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses by Jesse Schell. That’s one of the books that I’ve used in my current game design classes and it hits a lot of key points when thinking of the design process as an iterative loop. There’s also some great ideas on how to brainstorm ideas and how to think about risk mitigation. Or for animation there’s this amazing text book: The Animator’s Survival Kit: A Manual of Methods, Primciples and Formulas for Classical, Computer, Games, Stop Motion and Internet Animators by Richard Williams. The animation survival kit is an indispensable tool for both student and professional animators. Even if you are not an animator, it is a good study into form and movement in general.

As far as distribution, putting your game up for peer review can be absolutely essential. Getting as many people to play it and leave constructive criticism is extremely important. My suggestions would be to put your game up on such websites as Tigsource or GameJolt for free. Those websites are for developers to share their creations with other developers to get feedback and help on their designs. Improving them from iteration, which is a majorly important word in the gaming industry as a whole.

Documentation, documentation, documentation. Or as I like to call it “Learn from your past mistakes and your favorite games”. Something that is very good to do is to keep a large design document that records everything from your designs. From level design to the mechanics, story, art, everything, write it down and keep track of it. That will make things like creating a good game manual very easy. But more so, it allows other people coming into your company to figure out how and what your company is doing in terms of game design. It also gives you a chance to step back from your computer screen, allowing you to think about what decisions your designers are making and how they are impacting your game.

Something you should start doing immediately is reading postmortems. The industry news website Gamasutra has deep immersive archives of postmortems from everywhere in the industry. From small studios to large AAA companies, postmortems are essential to good game design. Postmortems catalog things that went right, went wrong, and ways to improve design in the future for every single video game title, attempt, and design. Writing and reading these can greatly improve decisions one makes when making a game.

GDC. The Game Developers Conference is another very important tool for all game designers, both amateur and pro. Not so much the convention itself, though if you have the opportunity and the capital to go (and it’s probably one of the most expensive conventions I’ve ever seen), by all means go. But the videos of the convention panels, which is called the GDC VAult, are extremely good resources for learning about game design. A free open list of all the videos GDC offers, a rating system for them, and a metric of “is the video worth watching” can be found here.

My final thoughts on The Last Specimen are that it’s a good first step into the world of game design, but it’s not worth $10, let alone being sold anywhere. The developers have a long and winding road that they need to travel before they get to the point to where they can be ready to sell a game, but with some hard work, good education, research, and practice, who knows what the future might hold.

![]()