WINEVILLE is a Barrel of Fun

Wineville (2023)

Written by Richard Schenkman

Produced by Richard Schenkman, Todd Slater, Robin DeMartino

Directed by Brande Roderick

Unrated, 1hr 39m

Wineville is the directorial debut of Brande Roderick (Baywatch, Celebrity Apprentice, Playboy), who also stars. Taking place in 1977, Wineville was once a real town where a horrific set of real killings took place. The Wineville Chicken Coup Murders took place between 1926 and 1928 and involved a mother, son, and nephew kidnapping, abusing, and murdering at least four boys before being caught. Claims of incest and abuse were lobbied by the accused as part of their defense during a trial so scandalous that the town of Wineville was renamed Mira Loma. Although mentioned in the movie as part of local lore, this is clearly where this movie’s DNA originated from.

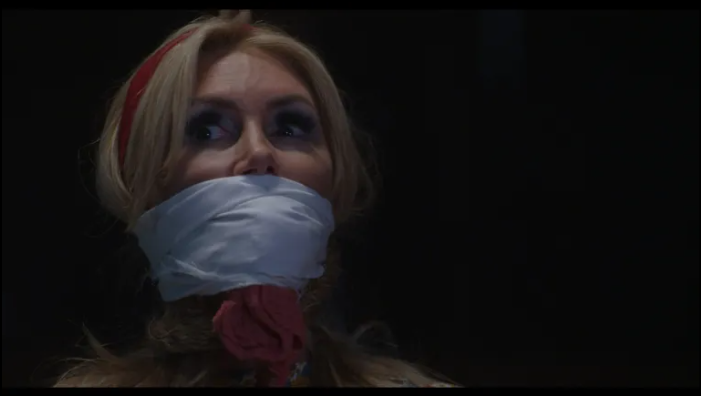

As with most horror movies, Wineville opens with a murder to set the stakes. A flirtatious woman is abducted after she attempts to help a handsome motorist and is swiftly and gruesomely dismembered.

Then the real movie begins: When Tess’s father, Edmund Lott (played by Will Roberts) dies, Tess Lott (Brande Roderick) travels from Las Vegas to return to the family winery in Wineville. She hasn’t been back since running away at sixteen and she is clearly not in the least bit upset by her father’s passing. Along for the ride is her young son, Walter (Keaton Roderick Cadrez, Brande’s actual son).

At the farm, Tess is reunited with her Aunt Margaret (Carolyn Hennesy), who is less than happy to see the now adult niece who ran away thirty years earlier. And she meets Joe Lott (Casey King), a family nephew and handyman who Margaret explains they took in and raised after she disappeared. He’s clearly the man we met during the open, abducting the woman. He seems charming and kind.

Walter is less than thrilled to be away from his home and stuck at some dusty farm, but he quickly is befriended by Joe, who shows him around the farm and many of its workings. Tess is eager to take ownership—since her father died without a will—and sell the farm, but Aunt Margaret is furious this will leave her homeless. For all Aunt Margaret’s viciousness towards Tess, Joe treats her and Walter nicely. While we expect nothing good to come from Aunt Margaret, Joe’s kindness manages to increase the tension, because his motives aren’t clear and while he seems like a genuinely nice guy—as opposed to someone pretending to be—the audience already knows he’s a threat.

Tess is haunted by her childhood experience at the farm, and as the movie progresses, we learn that she’s been molested by her father and given birth to his child—who Aunt Margaret said did not survive. Sexual and physical abuse abounds in Wineville, giving the victims their strength to run away or their fear to remain. Much like the gore as victims are dismembered, the images of abuse are carefully timed to linger long enough to discomfort the viewer, but not so long as to become gratuitous. Roderick is clear in her direction: she is using triggering topics to play chicken with the audience, and she’s not flinching first.

This is very much a throwback to the seventies horror genre, a specific niche of horror when practical effects had reached their pinnacle and every shot of gore needed to include pumping blood and every dismemberment displayed an understanding of anatomy. It also used themes of sexual abuse as motivation and oppression. Not all these themes have aged well.

During the flashback scenes, some of which are Tess’ memories and others are true flashbacks to events she couldn’t have been privy to, the screen narrows, and the movie gets the look, feel, and clacking projector sound of an old family movie. The first time it happened, I wasn’t sure why Roderick had chosen this method of delivery, but in a later scene we get to see how home movies relate to the abuse suffered by young Joe at the hands of Aunt Margaret. Roderick uses the film within a film technique not just to reveal a memory, but to portray trauma in a dissociative way. These are the moments that have played over and over in these character’s heads as they dealt with—but never recovered from their trauma. And while modern audiences may question the necessity of such scenes of incest and violence against women, it never strays too far from the very real themes presented by its source material—The Wineville Chicken Coop Murders.

There’s a lot to like in Wineville. It stays true to its seventies horror roots, so when a character is too likeable—I’m looking at you, Sheriff Hicks (Texas Battle)—expectation is enough to sense peril before any danger has truly focused on them. There are several attempts at jump scares throughout the movie. Rather than use them for cheap scares, Roderick uses them as a form of misdirection. The movie’s tension builds slowly, lulling the audience into a false sense of security, and the jump scares are both a reminder of the potential threats ahead and a suggestion that our expectations are misplaced. The movie unfolds well. There is never a moment that doesn’t have use to the story, so it’s one hour and forty-minute runtime feels well appropriated.

As the conclusion of the movie approaches and this disturbed family bonds, the threats and conflicts between them shift in subtle ways. There is a sense that the ending predetermined by the genre may not play out as expected. In the end, however, it does.

There is no surprise supernatural element responsible for this familial madness, no explanation beyond generations of abuse. While it drew Tess back, she was the only one strong enough to truly escape it. It’s a sad conclusion, one that turns biblically dark as the villains are dispatched. Nothing here is heavy handed, and the gratuitous images of gore become cathartic. This is no revenge story; the history of the family’s abuse comes abruptly and jarringly to a close. Compared to the original Wineville murders, you might say this movie has a happy ending.

![]()