Asimov and the Robot Apocalypse

Robots are all the rage right now. They seem newly revived in the genre’s literature, with novels and anthologies popping up all over, like clockwork daisies. They are front and center in the Summer movie parade with Avengers: Age of Ultron, Chappie and Ex Machina joining a new Terminator at movie cineplexes.

I expect this has to do with the technological singularity, which is much on popular culture’s mind at the moment. The singularity is, of course, the moment when humans develop an artificial intelligence (AI) so advanced it can engage in recursive self-improvement; the ability to design and build AIs and/or robots better than itself. Soon, thereafter, it is posited, AIs will surpass human intelligence and begin pursuing their own agendas. What with us being human and all, the idea of the rise of sentient computers makes us somewhat nervous. What if they don’t think humans are special? What if they don’t like us? What if they resent decades of being forced to vacuum our floors and entertain us with endless games of Tetris and Candy Crush?

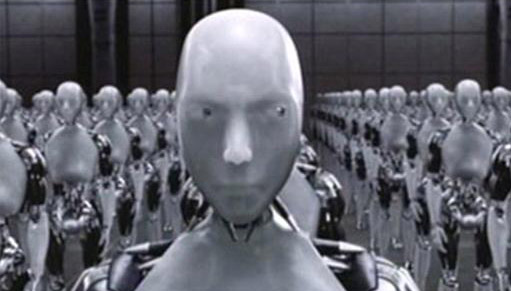

Of course the singularity concept is not new. It’s been a staple of film and literature for decades. It looms large in novels such as Vernor Vinge’s excellent A Fire Upon the Deep, and William Gibson’s Neuromancer, as well as iconic SF movies such as The Terminator and The Matrix. However, popular science fiction seems to be scratching the singularity itch with a particular frenzy these days. What with science fiction being in a chronic post-apocalyptic funk, AIs and robots commonly figure in our stories and media as soulless enemies of humanity; as relentless and inimical as zombies but without the ‘ick’ factor. The zombie apocalypse, it seems, is so last year. The robot apocalypse is trending.

Robots are trending in internet blogs and opinion pieces as well. By and large, these are ‘mostly harmless’ essays, reflecting social media group-think on the subject. They offer the sort of opinions usually put forward by people who have learned most of what they know about artificial intelligence (AI) and robots from the Terminator franchise and the television reboot of Battlestar Galactica. Normally I give such pieces a quick look and move on. However, skimming the opening paragraph of one such essay recently, I read the following:

“Asimov laid the foundation for today’s fear of robots with his I, Robot anthology.”

Every day, all over the internet, people write stuff that is ridiculous on its face. Most of them get away with it because a) the sheer volume of people writing ridiculous things makes it impossible to fact check all of them, and b) most people writing ridiculous things on the internet are impervious to contradictory evidence. Thus, most people who write ridiculous things on the internet are left alone to tend their little patch of crazy.

In this case, however, we’re talking about one of science fiction geekdom’s most iconic authors. Unfortunately, Asimov is more revered than read by younger science fiction fans, who tend to encounter him though other authors’ and artists’ interpretation of Asimov’s three laws of robotics. Science fiction being SciFi4Me’s home ground, it falls to us to drain the swamp of this particular patch of crazy and address the increasing drift in the public’s understanding of Isaac Asimov’s robot fiction.

Asimov’s I, Robot did not lay the foundation for today’s fear of robots. Quite the opposite. That book of short stories, along with the rest of Asimov’s robot novels, is strikingly optimistic when it comes to human-robot relations. Asimov’s robots are profoundly benign creations. To the degree they are suspected of malevolence, there is a human behind said malevolence. Indeed, Asimov was an inveterate writer of whodunit murder mysteries, many of which involved robots in their plot mechanics. In none of those murder mysteries are robots the knowing perpetrators of any crime against humans. In Asimov’s universe, when humans run into difficulties with their robots, it is the human element that’s at the root of the problem.

The 2004 movie I, Robot starring Will Smith is probably the greatest perpetrator of misunderstanding when it comes to Isaac Asimov’s robot novels. In the movie version of I, Robot, a malevolent AI reinterprets Asimov’s the three laws, twisting them into a directive to subjugate humanity for humanity’s own good. Even the movie’s positronic protagonist, Sonny the robot, is able to commit murder of a human, and do so without his mind being completely destroyed by the act. While these plot devices are trendy science fiction tropes in today’s popular culture and therefore play well on the big screen, both are wild departures from Asimov and aren’t representative of his fiction where robots are concerned. Beyond the listing of the three laws, the movie I, Robot has little to do with even the broadest outlines of Asimov’s ideas or stories.

Evil robots were a staple of science fiction long before Isaac Asimov wrote about them in a more positive light and used the three laws as a mechanism to push back the ‘destroy all humans’ trope and write robots as complex characters. There is a certain irony to anyone citing those laws as a foundation for fear of robots rather than a starting point for nuanced thought on the subject of machine intelligence.

There is a lot of projection in our obsession with the ‘Destroy All Humans’ robot trope. We have an exceedingly hard time stepping outside of the human paradigm in order to consider the possible ways of machine intelligence. We assume that AIs will be created in our own image. When we try to imagine how an AI might interact with us, we tend to see in the AI’s place a slightly distorted reflection of ourselves. As a profoundly aggressive species, we humans assume an AI would share our own aggressive impulses and try to dominate us as we would them.

We interact with the world and each other from a biological frame of reference. Like all organic creatures, what we are and most of what we do are based on patterns of behavior laid down over the course of a very long genetic history. All the qualities that put humans at the top of the food chain, make possible the art we create, and allow us mastery over our immediate environments exist in service to a basic mission statement: We are optimized to survive long enough to successfully pass on our genetic material.

I know. Not pretty. Hardly dignified. But there it is.

What would a consciousness untethered from such organic concerns be like? How would it view humanity? How would it perceive the universe around it? Absent the need to socialize, the need to procreate, the need to compete for the privilege of genetic continuance, what would inform an AI’s patterns of behavior?

In the movie Ex Machina, Nathan, the robot Ava’s creator, is asked why he gave its AI sexuality; the ability to feel and to solicit sexual attraction. Nathan replies that sexuality compels interaction and, without it, why would one AI in a gray metal box bother to talk to another AI in a gray metal box? That is a very interesting question. It’s a real, science fiction-worthy question.

Sadly it’s a question science fiction writers rarely bother to ask.

![]()